“Eastern Libya declares autonomy.” In spite of international headlines such as this one, talk of the country’s impending disintegration is misleading. Although the participants at the March 6 Barqa Conference (Barqa is the Arabic name for Cyrenaica, or the region of northeastern Libya) claimed the right to speak for their region, the initiative for self-administration and the move toward federalism triggered furious reactions in Cyrenaica. Given this lack of support in the region itself, the push is unlikely to succeed.

Foreign media coverage of reactions to the initiative focused on anti-federalism demonstrations in Tripoli and the angry response of the chairman of the National Transitional Council, Mustafa Abdul Jalil. But this emphasis on the tension between the central government and proponents of northeastern autonomy is misguided. More important were the reactions against the decisions in the northeast itself. The local councils of the area’s major cities – Benghazi, Darna, Bayda and Tobruk, which also saw large demonstrations against federalism – all immediately made clear their opposition to the Barqa Conference’s declaration and refused to recognize its proposed regional council.

In addition, the Muslim Brotherhood – which has an important base in northeastern Libyan cities – called the declaration the work of narrow-based and personal interests. Furthermore, the initiative has not received significant backing from the disparate armed entities that are controlling the northeast. For instance, the region’s most powerful militia grouping, the Union of Revolutionary Brigades (Tajammu Saraya al-Thuwwar), opposed the conference, and the Barqa Military Council (an unofficial grouping of several army units situated in the region) distanced itself from the conference, declaring that it would not get involved in politics.

Proponents of federalism undoubtedly have an influence in Cyrenaica – perhaps more so than in other regions. Leading figures at the Barqa conference included tribal notables as well as intellectuals. The most prominent of these was Ahmad Zubair al-Sanusi. He is a member of the royal family that ruled Libya from 1951 to 1969, and was appointed to head the regional council. But without the local support of the region it claims to govern, the regional council has little chance of actually governing Cyrenaica.

That the Barqa conference even attempted to exploit the constitutional vacuum to single-handedly set up a ruling body is symptomatic of both the fragility of the current transition and the National Transitional Council’s own weakness. Itself a self-appointed body, the National Transitional Council has faced a wave of criticism regarding its sluggish tackling of urgent problems in Libya.

But the backlash seems directed more against the very concept of autonomy, which is perceived by many Libyans as a harbinger of national disintegration – despite the insistence of leading pro-federalism figures that they do not seek full independence and have no plans to control the region’s oil revenues or set up a regional army.

Conspiracy theories have begun circulating regarding the alleged involvement of foreign powers (as suggested by the National Transitional Council chairman, Abdul Jalil). Additionally, opponents of federalism have seized on the involvement in the federalism call of several organizers in the former regime. For example, Wanis Sharif, an Interior Ministry official, accused Al-Tayyeb al-Safi (a once-prominent figure in Moammar Gadhafi’s Revolutionary Committees) of paying Egyptians to demonstrate in Benghazi in favor of federalism. Safi’s brother, Abu Bakr, is purported to have been a leading sponsor of the Barqa Conference. In this climate of suspicion, armed clashes broke out in Benghazi on March 16 between supporters of the movement and its opponents.

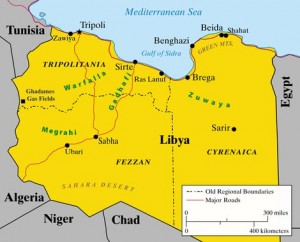

Yet beyond the immediate reactions, there are deeper reasons why these aspirations are unlikely to gain much support. Augurs of disintegration often point out that Libya only emerged as a single entity under Italian colonial rule, and that even after its independence in 1951, Libya was divided into three distinct regions – Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Fezzan. Each of these regions was controlled by local notables and tribal leaders, and had their own representative assemblies and administrations.

Although the Barqa Conference explicitly sought to resurrect this system, the regional entities introduced in 1951 were (even then) novel concepts for local tribes, who until that point had been largely outside the reach of the state’s administration. Moreover, after the onset of oil production greatly enhanced the central government’s power, federalism was soon abolished in 1963.

This past year’s civil war saw the emergence of local councils and militias representing the specific interests of towns, cities and tribes. As a result, political and military organization during and after the conflict has generally been at this level – rather than visible on the regional or national levels. While Zintan and Misrata developed into military and political heavyweights – with Misrata home to dozens of different militias – almost all large Libyan towns have their own brigades and military councils now. With its army and security apparatus in disarray, the government is largely unable to exercise territorial control in the face of the local forces, and is making only slow progress in re-establishing authority over border posts and airports – some of which continue to be controlled by militias.

It is at this local level that politics is most dynamic. On Feb. 20, Misrata elected a new local council after protests similar to the ones against the National Transitional Council; other major cities are to follow with local council elections in the coming weeks – Benghazi in April, and Tripoli in May. These are spontaneous local initiatives.

In contrast, national forces are still in their infancy, and new political parties have only mushroomed over the last few months. In early March, for example, Libya’s Muslim Brotherhood joined together with other moderate Islamist figures to form the Justice and Construction Party (Hizb al-Adala wal-Bina). However, local figures seem likely to dominate the June elections for the General National Assembly, where most of the representatives are to be chosen on the basis of individual constituencies. The delineation and weight of these constituencies has yet to be announced and could become a contentious issue for towns that perceive themselves to be underrepresented.

The dominance of locally based interest groups is also reflected in the recent clashes that have pitted militias from different towns or tribes against each other nationwide. In many cases, conflicts run along the divisions of the civil war, reflecting the fact that Gadhafi’s security apparatus was recruited from certain tribal constituencies rather than others. Attempts by one group to arrest or disarm members of another group have been among the most common triggers of such clashes, which have been more pronounced in western and southern Libya than in Cyrenaica – though rivalry has increased even there.

Following the announcement of the current government this past November, representatives of the Magharba and Awaqir clans demonstrated in Benghazi to demand greater political representation for their tribes. Leaders of the Obaydat tribe have clashed with other militia leaders in Benghazi over the slow progress of the investigation into the July 2011 murder of Major-General Abdul Fatah Younis Al-Obeidi, the former head of the Free Libyan Army. The Obaydat have repeatedly threatened to close roads or oil export terminals to exert pressure on others. In this environment, it remains difficult to imagine these different groups jointly pushing for regional unity – much less autonomy.

The local power centers seem more likely to push for the decentralization of the decision-making process to the local level. This would involve moving control of budgeting processes to towns or districts and thus cementing the influence those cities, towns, and tribes acquired during the civil war. Contrary to federalism, decentralization appears to enjoy widespread support – even within the central government, which has already committed to delegating authority to local councils.

The National Transitional Council only recently extended the timeframe for the Constitution-drafting process to four months, which is due to start after the elections planned for June. In a situation where there is no previous Constitution to build on (excluding the one in force during the monarchy) this is an extremely short timeframe.

That the debate over decentralization, federalism, and the role of local political entities has begun already is a welcome sign. But the sudden – though unsubstantiated – push at Barqa only proves that nothing can be taken as given in the negotiations over the fundamental tenets of Libya’s future government.

(Source: The Daily Star)